Although great care has been taken in the compilation and preparation of all directory entries to ensure accuracy, we cannot accept responsibility for any errors or omissions. Any medical information is provided for education/information purposes only and is not designed to replace medical advice by a qualified medical professional. Please see our disclaimer at the bottom of this entry.

What are fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter species?

Fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter species are a type of Campylobacter species resistant to fluoroquinolones, antibiotics used to treat a lot of bacterial infections. Unfortunately, the high rates of resistance to fluoroquinolones have limited their usefulness in treating Campylobacter infections, as well.

What are Campylobacter species?

To understand fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter species, it is important to know what Campylobacter species are.

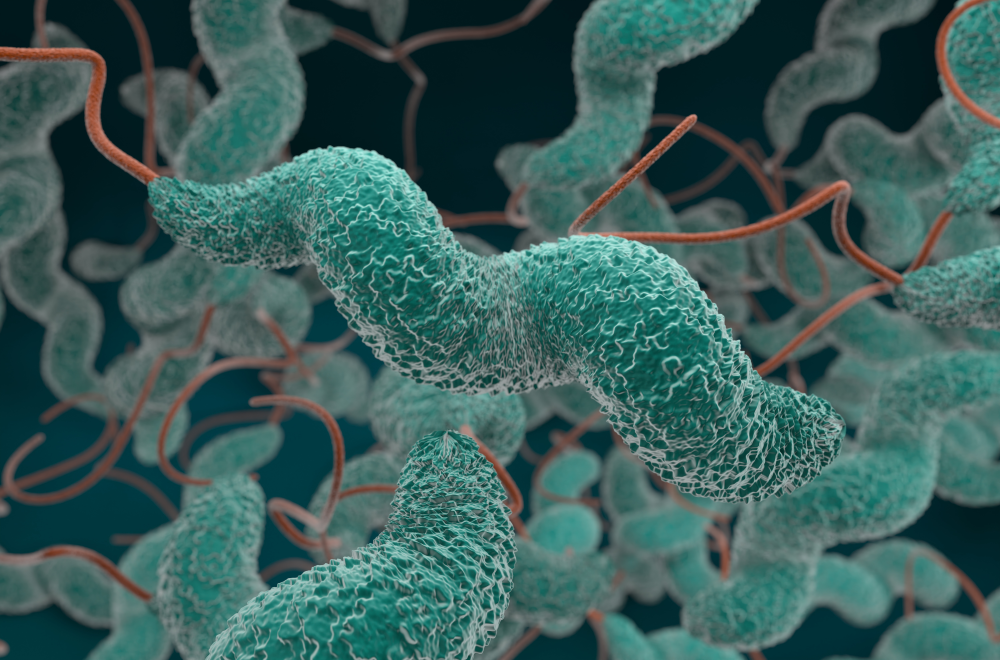

Campylobacter are gram-negative bacteria. When observed under a microscope, they are corkscrew, rod-shaped, and typically tend to move. There are several species of Campylobacter, and Campylobacter jejuni is the most commonly implicated species in human infections.

Campylobacter species can cause gastroenteritis, but also life-threatening conditions in people with a weakened immune system (see Who is at risk of a Campylobacter infection).

Where can Campylobacter be found?

Campylobacter bacteria normally live in the intestines of many farm animals (including cattle, sheep, pigs, chickens, turkeys), and pets, such as cats and dogs. Therefore, the feces of these animals may contaminate water, milk, meat, and other foods.

How can Campylobacter spread?

It takes very few Campylobacter bacteria to make someone sick, and people may be infected in several ways:

• Drinking contaminated water. Indeed, water from lakes and streams can be contaminated by animal feces.

• Drinking unpasteurized raw milk or dairy products. Milk can be contaminated if a cow has a Campylobacter infection in her udder, or when milk is contaminated with manure. Pasteurization makes milk safe to drink.

• Eating raw or undercooked meat (usually poultry, but also other foods, such as seafood, and produce). Indeed, Campylobacter can be carried in the intestines, liver, and other organs of animals, and can be transferred to other parts when the animal is slaughtered.

• Eating food prepared on kitchen surfaces touched by contaminated meat.

• By contact with dog or cat feces.

Which infections can Campylobacter cause?

Campylobacter bacteriacan cause gastroenteritis. People with Campylobacter infection usually have diarrhoea (which may be watery, sometimes bloody), and abdominal pain, accompanied by fever, headache, nausea and vomiting. These symptoms usually start 2 to 5 days after the person ingests Campylobacter, and continue for about one week.

Most people completely recover within a week, but these bacteria can cause life-threatening infections in people with weakened immune systems (see Who is at risk of a Campylobacter infection). Indeed, microorganisms can occasionally spread inside the bloodstream (bacteremia), and infect other sites in the body, such as the joints (infectious arthritis).

Campylobacter infection rarely results in long-term health problems. However, peripheral nerves may be affected (polyneuropathy), causing the so-called Guillain-Barré syndrome, a medical condition with muscle weakness or sometimes paralysis that can last for weeks, and often requires intensive medical care.

Who is at risk of Campylobacter infections?

Anyone can develop a Campylobacter infection, but certain groups of people are at greater risk than others to develop serious conditions, including:

• infants and young children,

• adult aged 65 years or older,

• pregnant women,

• people with a weakened immune system, such as from HIV, immunosuppressants (medications which slow or stop the response of the immune system), or cancer chemotherapy.

How are Campylobacter infections diagnosed?

To correctly diagnose an infection caused by Campylobacter bacteria, first of all your physician will perform a physical examination and ask you about symptoms and risk factors. Guided by these elements, your doctor will be able to choose the most appropriate diagnostic tests.

Laboratory tests can identify Campylobacter using a sample taken from stool. These samples are sent to a laboratory to grow the microorganism over time using a media on a petri dish (culture) and identify it. Then susceptibility tests can be carried out to determine which antibiotics are most effective against it, to start the most appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Understanding which antibiotic will work best is especially key to fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter species as these types of resistant Campylobacter bacteria may only respond to certain medicines.

Finally, depending on the severity of infection, your physician may recommend additional tests, such as imaging tests.

How are Campylobacter infections treated?

Most people recover from Campylobacter infection without antibiotic treatment. Patients have to drink extra fluids as long as diarrhea and vomiting last in order to avoid the risk of dehydration. However, people with, or at risk for, serious illness may need an antibiotic therapy.

The antibiotic may vary according to the results of susceptibility tests. Indeed, some infections, such as those ones caused by fluoroquinolone-resistant Campylobacter species, are resistant to this type of antibiotics.

Depending on the site and the severity of infection, the medication could be in the form of tablets to swallow. However, severe infections require to be treated in hospital with intravenous antibiotics (the medication is given through a drip or a tube), and additional therapies.

Due to the increasing resistance to the available antibiotics, Campylobacter infections are becoming more and more difficult to treat.

How can Campylobacter infections be prevented?

Following these precautions can lower your risk of getting a Campylobacter infection. Moreover, they help to reduce your chances of spreading bacteria to others, as well.

• Wash your hands thoroughly and regularly with soap and running water. Keeping your hands clean is particularly important before, during, and after preparing food; before eating food; after using the toilet; after changing diapers; after blowing your nose, coughing, or sneezing; before and after caring for someone who is sick; after touching pets and other animals or their food or stool; after touching garbage. Remember: hand hygiene is your best protection against infections.

• Keep raw poultry away from other foods. Use separate cutting boards for raw meat, and clean them properly. Clean all countertops, and utensils with soap and hot water after preparing any type of raw meat.

• Cook food to the right temperature. Be careful especially with poultry (chicken, turkey, duck, goose, and other farmed birds).

• Washing or scrubbing fruits and vegetables before eating.

• Only drink pasteurized milk.

• Do not drink untreated water.

• Take care with pets. Pets sometimes carry Campylobacter and other microorganisms that can make you sick.

Disclaimer: The information provided on this website is intended for educational purposes only. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. Reliance on any information provided on this website is solely at your own risk. The website owners and authors are not responsible for any errors or omissions in the content or for any actions taken based on the information provided. It is recommended that you consult a qualified healthcare professional for individualised medical and health-related guidance.