Although great care has been taken in the compilation and preparation of all directory entries to ensure accuracy, we cannot accept responsibility for any errors or omissions. Any medical information is provided for education/information purposes only and is not designed to replace medical advice by a qualified medical professional. Please see our disclaimer at the bottom of this entry.

What is a surgical site infection (SSI)?

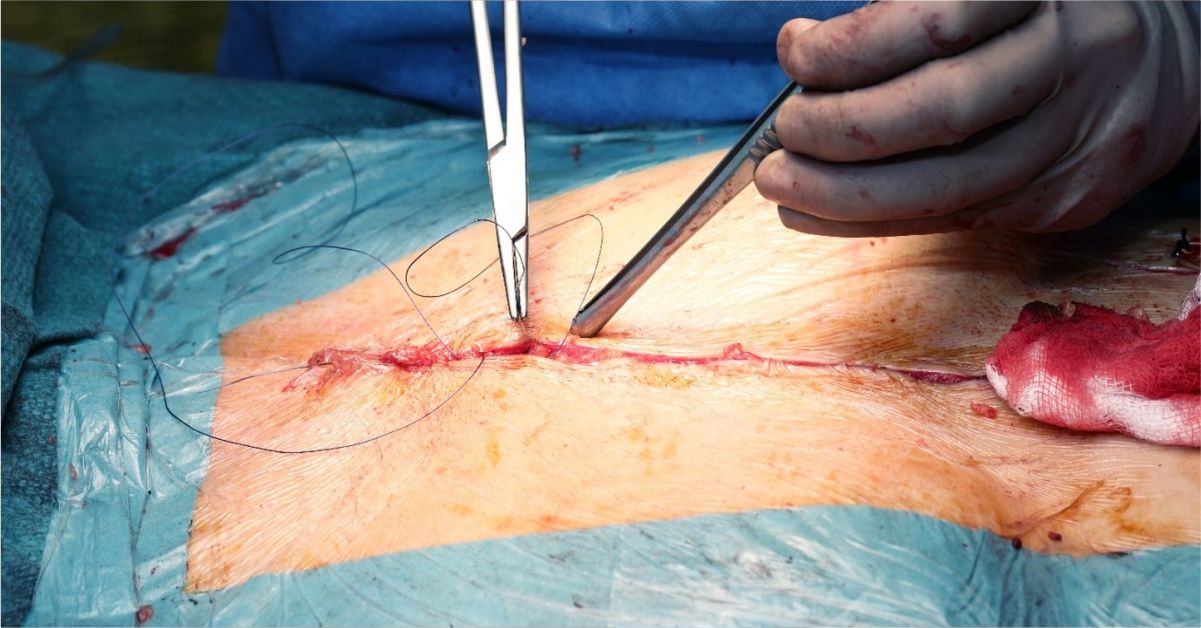

A surgical site infection (SSI) is an infection that occurs after surgery in the part of the body where the operation was performed. SSIs are among the most common healthcare-associated infections.

Most surgical wounds heal up rapidly, and only a minority of them are complicated by an infection (an SSI may develop in around 1% to 3% of patients who undergo a surgical procedure). An SSIs typically show up within 30 days after surgery, and very occasionally, can occur several months after an operation.

SSIs may be superficial and limited to the area of the skin where the incision was made. However, infection can occasionally spread deeper, involving tissues and muscle under the skin, organs, or implanted material.

Some SSIs, not all, may be difficult to treat because of the increasing rise of pathogens (germs) becoming resistant to antimicrobial medicines.

How do patients get an SSI?

An SSI occurs when germs (such as bacteria or fungi) enter the cut in the skin where the surgery has been performed.

The skin is a natural barrier which normally prevents microorganisms from entering the body, but the break in the skin due to surgical incision may allow them to enter and cause an infection.

Surgical wounds may be infected by germs that are already on the skin, or are inside the body or from the organ on which the surgery was carried out, or are in the environment.

Who is at risk of getting an SSI?

Anyone can develop an SSI, but certain groups of people are at greater risk than others, including:

• smokers;

• people overweight or obese;

• people with chronic illnesses, such as cancer or diabetes;

• people with a weakened immune system, such as from immunosuppressants (medications which slow or stop the response of the immune system), or cancer chemotherapy;

• people who have surgery that lasts longer than 2 hours;

• people who have emergency or abdominal surgery.

What are the symptoms of an SSI?

Some of the most common symptoms and signs of an SSI are the following:

• redness, tenderness, and pain around the area where the surgical procedure has been performed;

• discharge of cloudy fluid from the surgical wound;

• fever.

How is an SSI diagnosed?

To correctly diagnose an SSI, first of all your physician will perform a physical examination and ask you about symptoms. Guided by these elements, your doctor will be able to choose the most appropriate diagnostic tests.

Your physician may take a sample from the surface of your wound with a swab. Then, this sample is sent to a laboratory to grow the microorganism over time using a media on a petri dish (culture) and identify it. Then susceptibility tests can be carried out to determine which antimicrobials are most effective against it, to start the most appropriate antimicrobial therapy. Understanding which antimicrobials will work best is especially key to SSIs as antimicrobial resistance among pathogens is a constantly growing problem.

Finally, depending on the site of infection, your physician may recommend additional tests, such as imaging tests.

How is an SSI treated?

Guided by the symptoms and the results of diagnostic tests, your physician will determine the best treatment for you. Antimicrobials, such as antibiotics or antifungals, may be used to treat an SSI.

The antimicrobials may vary according to the type of the infection, the microorganism responsible of the disease, and the results of susceptibility tests. Depending on the site and the severity of infection, the medication could be in the form of tablets to swallow. However, severe infections require to be treated in hospital with intravenous antimicrobials (the medication is given through a drip or a tube), and additional therapies.

Moreover, your surgeon may decide to perform an additional surgical procedure to clean the wound.

Unfortunately, due to the increasing resistance to the available antimicrobials, SSIs are becoming more and more difficult to treat, and sometimes a combination therapy is needed (it means that two or even more antimicrobials are necessary).

What can patients and caregivers do to help prevent an SSI?

Patients with a surgical wound and their caregivers can take the following precautions to help prevent an SSI:

• Understand how to care for your surgical wound.

• Always clean your hands before and after caring for your wound (by washing them with soap and water or using an alcohol-based hand rub). Remember: hand hygiene is your best protection against infections.

• Ask people who visit you to clean their hands, and not to touch the surgical wound or dressings.

• Ask your health professionals if they have washed their hands before touching your surgical wound.

• If you suspect to have symptoms or signs of infection, call your doctor immediately.

Disclaimer: The information provided on this website is intended for educational purposes only. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. Reliance on any information provided on this website is solely at your own risk. The website owners and authors are not responsible for any errors or omissions in the content or for any actions taken based on the information provided. It is recommended that you consult a qualified healthcare professional for individualised medical and health-related guidance.